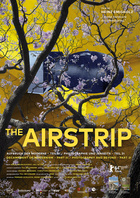

THE AIRSTRIP

Photographie und jenseits – Teil 21

Photography and beyond – Part 21

Aufbruch der Moderne – Teil III

Decampment of Modernism – Part III

Film von Heinz Emigholz

D 2013, HDV, 108 min

Press Downloads

Download Stills

Regie: Heinz Emigholz

Buch, Kamera: Heinz Emigholz

Sprecherin: Natja Brunckhorst

Mann am Strand: Ueli Etter

Musik: Kreidler

Kameraassistenz: Till Beckmann

Schnitt: Heinz Emigholz, Till Beckmann

Originalton: Till Beckmann, Heinz Emigholz, Ueli Etter, Lilli Kuschel, Markus Ruff, Christin Wilke

Tongestaltung: Jochen Jezussek, Christian Obermaier

Tonmischung: Jochen Jezussek

Postproduktion, Animation: Till Beckmann

Produktionsassistenz Europa: Markus Ruff, Alex Jovanovic, Lilli Kuschel, Luca Pisciotta, Katharina Zollner

Produktionsassistenz Südamerika: Laura Bierbrauer, Elisa Miller, Lukas Rinner, Christin Wilke

Produktionsassistenz Saipan: Ueli Etter

Musik: 'Moth Race', 'Sun' und 'Rote Wüste' von Kreidler (Alex Paulick, Thomas Klein, Andreas Reihse , Detlef Weinrich)

Film im Film: 'An Bord der USS Ticonderoga' von Heinz Emigholz mit einer Photographie von Wayne Miller

Redakteur: Reinhard Wulf

Produzenten: Frieder Schlaich, Irene von Alberti

Gefördert von BKM - Beauftragter für Kultur und Medien, Medienboard Berlin-Brandenburg, Filmförderung Hamburg-Schleswig-Holstein

Koproduziert mit WDR

Produziert von Filmgalerie 451

Dank an

Francesca Andreoli, Susanne Anger, Laura Costa, Riccardo D’Andrea, Maximiliano Franconieri, Roswitha Hennig, David Moore, Ulrich Müther, Nestor Pan, May Rigler, Alina Rojas, Daniel Saltzwedel, Christián Stupp, Hans Thalgott, Agnieszka Wardawa, Adriana Williams und Akademie der Künste Berlin, Club Atlético Boca Juniors, Film Commission Bologna, Hala Stulecia Wroclaw, Italienische Botschaft Brasilia

Trailer

Musikvideos SUN, ROTE WÜSTE und MOTH RACE von Heinz Emigholz für KREIDLER

Musikvideopremiere von MOTH RACE bei Spex.de

"MuVi-Preis für das beste deutsche Musikvideo" für MOTH RACE auf den Kurzfilmtagen in Oberhausen 2013

About the film

Imagine an airspace into which a bomb has been dropped. The bomb has not reached the site of its detonation, but there is no way to stop its speedy approach. The time between the bomb’s release and its explosion is neither the future (for the ineluctable destruction has not yet happened) nor the past (which is unavoidably about to be extinguished). The flight time of the bomb thus describes absolute nothingness, the zero hour, consisting of all the possibilities that in just a moment will no longer exist. Thus, this story will end before it has begun; here it is told in defiance: an architectural journey from Berlin through Arromanches, Rome, Wrocław, Görlitz, Paris, Bologna, Madrid, Buenos Aires, Atlántida, Montevideo, Mexico City, Brasilia, Tokyo, Saipan, Tinian, Tokyo, San Francisco, Dallas, Binz and Mexico City back to Berlin – into the abyss.

Buildings and sculptures

The film The Airstrip was shot from March 2011 to June 2012 in Germany, Italy, France, Spain, Argentina, Uruguay, Mexico, Brazil, the United States, the Northern Mariana Islands and Japan. It shows the following buildings and sculptures:

Prometheus Bound (1899) by Reinhold Begas in Berlin, Germany

Mulberry Harbour (1944) by Winston S. Churchill in Arromanches, France

Pantheon (2nd century AD) in Rome, Italy

Hala Ludowa (1913) by Max Berg in Wrocław, Poland

Department Store (1913) by Carl Schmanns in Görlitz, Germany

La Vache Noir Shopping Centre (2000s) in Arceuil, France

Gustave Eiffel Monument (1928) by Auguste Perret in Paris, France

Market Hall (1953) by Renato Bernadi in Bologna, Italy

Madrid Airport

Mercado de Abasto Shopping Centre (1934) by Viktor Sulčič in Buenos Aires, Argentina

La Bombonera Stadium (1940) by Viktor Sulčič and José Luis Delpini in Buenos Aires, Argentina

Three Mausoleums (1930s and ’40s) by Viktor Sulčič on the Recoletta Cemetery in Buenos Aires, Argentina

Parochial Church (1960) by Eladio Dieste in Atlántida, Uruguay

Warehouse (1979) by Eladio Dieste in Montevideo, Uruguay

Montevideo Airport

Las Arboledas (1958-63) by Luis Barragán in Mexico City, Mexico

Double House (1937) by Luis Barragán in Mexico City, Mexico

Towers on the Queretaro Highway (1958) by Luis Barragán and Mathias Goeritz in Mexico City, Mexico

The End of a Highway (2012) in Mexico City, Mexico

Mexico City Airport

Italian Embassy (1959) by Pier Luigi and Antonio Nervi in Brasilia, Brazil

Brasilia Airport

Tokyo Airport

Japanese Prison (1930s) in Garapan on Saipan, Northern Marianas

La Fiesta Shopping Centre (1990s) on Saipan, Northern Marianas

Monument on the Banzai Suicide Cliffs (1953) on Saipan, Northern Marianas

Saipan Airport

Northfield Memorial (1985) on Tinian, Northern Marianas

Tokyo Airport

Saint Mary’s Cathedral (1971) by Pier Luigi Nervi in San Francisco, California

Dallas Airport

Bus Stop (1967) by Ulrich Müther in Binz, Germany

Cathedral (1573-1813) in Mexico City, Mexico

Neptune Fountain (1891) by Reinhold Begas in Berlin, Germany

Don’t ask about sunshine.

A saying of my father Heinrich Emigholz

A Journey to Saipan

I can name the exact moment. It was the afternoon of 23 October 2010 when, after all those years, I resolved to fly to the Northern Mariana Islands, to Saipan, from there to cross over to Tinian. Those who not only have heard of Pearl Harbor, but also wince at the names of Midway, Wake, Marcus, Marshall, Kwajalein, Eniwetok, Gilbert, Truk, Iwo Jima, Attu, Kiska, the Salomons, Bougainville, Rabaul, Ulithi, Guadalcanal, Espiritu Santo, Guam, Palau, Mindanao, Luzon, Tarawa and Okinawa, will understand this decision. I confess that I owe my life to the first two atom bombs and, as a German, to the Japanese fanaticism that led to their being dropped on Japan. But now I wanted to be where it all culminated, in the western Pacific. I felt like a turtle that swims back thousands of miles to the place of its birth to bury its eggs in the sand – on the beach where many soldiers had to die, soldiers to whom I owed my life and a childhood sheltered by the balance of terror.

Life, if it lasts long enough, is easier to narrate as a frame tale. This literary form was conceived to propagate meaning, even if, as solace, it consists solely of distant echoes. In the 1950s, the two cinemas in our small town – the Corso and the Odeon – were full of American B movies about the war in the Pacific. Alternating with films with Fuzzy, these black-and-white films could be seen there almost every Sunday. My first confrontation with Anatahan, by Josef von Sternberg, later my favourite film and favourite director, also came at this time. The first face of an actor that lastingly inscribed itself in my consciousness, along with that of Al St. John as ‘Fuzzy’, was Lee Marvin’s, who appeared in many of these films as the sturdy rock in the midst of battle. While shooting our film in Saipan, I learned that Marvin, a US Marine, had been awarded a Purple Heart for being severely wounded in the assault on Mount Tapochau on Saipan in June 1944. There is something about this island.

While researching for the film Parabeton, I had run across the book The Roman Pantheon: the Triumph of Concrete by the American civil engineer David Moore. In it, he describes the recipe for Roman cement and the construction art of the Roman construction legionnaires. Moore’s website has two other topics: the prostate cancer of war veterans and The Battle of Saipan, in which Moore took part as a ‘Seabee’ in June 1944 – as one of the pioneers of the US Navy Construction Battalions that built the airfields on Saipan.

On 20 July 2009, William Styron’s autobiographical story Rat Beach appeared in The New Yorker. I read it because Styron had saved my life in 1990 with his elucidations on the ‘Black Dog’ – a term Churchill found for his depressions – in his book Darkness Visible. Reading Rat Beach was staggering und crucial for my decision of 23 October. In Spring 1945, as a 20-year-old officer, Styron had to train his unit to land on Japan’s home islands. His text describes his mortal fear in the face of a fanatic, desperate enemy who would stop at nothing. He describes the roar of the motors of the B-29s taking off day after day from Tinian, the neighbouring island to the south, to bombard Japanese cities. Among them were the two B-29 Superfortresses, the Enola Gay and the Bockscar, with the atomic bombs Little Man and Fat Man on board; dropping them saved not only his life.

On my return flight from Saipan to Tokyo, I glimpsed a rainbow over the volcano, active again since 2003, on the neighbouring island to the north, Anatahan. I decided to shoot the film Anatahan II as a sequel to The Airstrip. The only architectures on it are huts, caves and those of the plants. Unless the people who occasionally visit the island, uninhabited since 1990, count as buildings.

Heinz Emigholz

Photography and Beyond – State in 2013

After the premiere of The Holy Bunch at the Forum of the Berlinale on 17 February 1991, I was in a precarious situation. Along with a few intelligent commentators, the film’s comfortable robustness and cool narrative elegance had driven Germany’s film-journalisting widow chasers up the wall. The Sputnik film distribution company did its best for the film, but in the end I, the film’s sole producer, was more bankrupt than ever before. Munich’s film-funding oligarchs, who dominated the scene at that time, stopped cold the successor project initiated by Manfred Salzgeber, a film version of Hans Henny Jahnn’s novel Fluß ohne Ufer, for which Klaus Behnken, Ueli Etter and I had worked up a production-ready script. After ‘discovering’ me in 1991 at the Cannes Film Festival (in turn after I had ‘discovered’ his wife, the wonderful Dana Vavrova, for one of the roles in Fluß ohne Ufer), Joseph Vilsmaier cast me in a few lucrative supporting roles, rescuing me from financial ruin. My alienation from film in general, however, was never greater than at that time, and I swore to myself I would quit – or start over from the beginning.

My new beginning came in 1993 with the project Photography and beyond, which Wilfried Reichart, a producer at WDR TV-station and a fan of The Holy Bunch, let me make. Reinhard Wulf, also from WDR, and various film subsidies sustained this collaboration with Filmgalerie 451 and Amour Fou Vienna. But at the time I had no idea how long this project would keep me busy. Here is an excerpt from the project description of the time: ‘Photography and beyond is a film project about writing, drawing, sculpture and architecture. The film’s theme is the active work of design and projection – imaginings that have become real. A process of reversed seeing, so to speak, is analysed: seeing as expression, rather than impression. The eye as interface between brain and external world, the gaze as a composing force that turns the inside out and presents it in reality in a mirror image.’

Photography and beyond was initially supposed to be a film essay of about 100 minutes in which I wanted to explore the facts of a designed world and its appearance on cinematographically designed depiction surfaces. Architectures, sculptures, photographs, drawings, paintings, writings, cinematography, collages, prints and urban landscapes were on the list of motifs. The story would not be told by means of language or dialogue, but through the depicted things and situations themselves. Not exactly a project for the BBC or the History Channel and their soft-boiled kind of documenting; I began calling the resulting films ‘hard-core documentations’. Because it didn’t stop with a single film. After a footage-shooting phase that lasted years and then an editing block – and an interlude to establish an Institute for Time-Based Media at the University of the Arts in Berlin – finally in 2001, initially three short films were released under the overarching title Photography and beyond. Constant cell division on the list of motifs and the new collaboration with Artimage in Graz then led to many more short and long films. Now, twenty years after the beginning of this enterprise, ten long and seventy-four short films are on the project’s back catalogue list. These films are characterised and were made possible by rigorously eliminating any inflated production apparatus and concentrating all means on the desired and ultimately crucial visual and acoustic cinema experience. A list of the films with accompanying descriptions and commentaries can be viewed at www.pym.de and www.filmgalerie451.de. I presented the further epistemological implications of the series in the footnotes to the text The End in Disko 22 at www.a42.org.

Most of the films in the series so far have been concerned with architecture, giving the project a certain unintended imbalance. In point of fact, the architectonic studies and field research are finished with the new films Two Museums and The Airstrip – apart from three long-term projects that will keep me busy for some years more. At first, catalogue of the works of my favourite Classical Modernist construction engineers and architects (Sullivan, Maillart, Loos, Schindler, Perret, Goff, Nervi) stood in the foreground of my interest; but triumphing in the end was the cinematographer’s interest in anonymous architectonic situations that can no longer be attributed to a known designer.

It would be the fulfilment of a utopia if I were given an annual budget with no earmarks; I would return the favour with at least two architecture films shot around the world: a comedy and a tragedy. I am sure that everything people can narrate can be found in architecture: their love for one another, their fears of one another, their desire for protection and outfitting, their embedding in the circle of nature. Not least, an uproarious comic aspect inherent in architecture is underestimated all over the world. Unfortunately this utopia cannot be fulfilled, because the advance financing of films feels committed to the word and not the image.

Heinz Emigholz

Interview with the Director

You’ve been working on the series Photography and Beyond for more than twenty years now. The series’ architecture films have never been solely about architecture or individual architects; they are equally films about cinema, yourself as an author and what constitutes our own perception. Their structure was almost always the same: a chronological sequence of pictures of constructions with the dates when they were built and when the footage was taken. The buildings determined your travel itinerary. This time was different: your route took you to very disparate constructions and, as you put it, into the abyss. What happened? And how does that express a new relationship between architecture and cinema?

The film is the product of a wish I’d had for a long time and at the same time of a necessity. It was necessary to deal with the remnants or the beginnings of a film on the oeuvre of Luis Barragán, which we couldn’t continue because of the horrendously expensive rights to picture his works. All that remained of him are the objects in public space, which no one could forbid us from filming. For me, that was a blessing in disguise. Focusing solely on his rather design-dominated oeuvre would have robbed me of a quintessence in the series of architecture films. I always wanted to work in freedom, and I suggested to my producer, Frieder Schlaich of Filmgalerie 451, to take an extended trip around the world and document a list of architectures or architectonic ensembles whose later sequence in film would make broader sense. A miscellanea film, so to speak, with a pointed emphasis on how the ideological-sculptural kitsch of Wilhelmine German developed a destructive fury that spanned the world and simply divided architectures into pre-war, wartime, post-war and guilt architectures. That Frieder Schlaich made it possible for me to make The Airstrip – after Parabeton and the Perret film, which were both financed from the same budget earmarked for a single film – speaks for our economical way of working, on the one hand, and, on the other, for his willingness to take risks and his strong personal interest in the long-term project. But also for the insight that we had finish it before we could produce feature films together again. For me, the ‘abyss’ is the eternal cycle of destruction and new beginnings – full of pathos, brutality and victims. A spiral of what is always the same: construction, catastrophe, destruction, adversity, reconstruction, all the way to the incredibly idiotic reconstruction of Berlin’s City Palace in the name of a ‘tradition’ based on mayhem. Film can tell the story of the mortal fates that get caught in this spiral.

This Internet age gives new meaning to someone’s journey around the world to make pictures. When you capture a building with the camera, you describe it as a process that makes it possible to cinematically participate in the direct experience of spaces. Can this space of experience be transferred to the process of traveling in several countries? On the path from the series’ previous films to The Airstrip, did you feel a threshold between the documentary film and what I wouldn’t call fiction, but writing philosophy?

The travels and their results are also a reply to what is or was to be found in the net. Each new medium includes all the ones that went before, but to a certain extent, at least at first, it also takes on their flaws and aesthetic norms. On the one hand, there is the cult of the ‘representaive’ picture, which dominates in architecture photography, and on the other hand, there is the ‘snap-shot’ image, which in some minds still stands for ‘authenticity’. To depict the subjective response to a particular architectural situation is an authorial act and demands a direct confrontation with the object; it can’t be adopted second-hand. ‘Documentary film’, like ‘experimental, avant-garde, underground, feature, or whatever film’, is caught in a web of unspeakable attributions and definitions. Unfortunately, too often they prevent one’s own, analytical and philosophical access to the situations depicted. The same goes for film-technical questions of format, which have their place but remain marginal, unless one wants to devote oneself to nostalgia. These genres took form essentially in a Western cultural context that certainly can’t always be equated with the ‘Enlightenment’. Cementing the idea in the academic world doesn’t help, either. Interaction with other, local and non-simultaneous cultures that are not ‘ours’ exposes some avant-garde airs as lofty nonsense. What we essentially still have to offer the world is the consciousness of ‘critical customers’ educated in capitalism.

The radically subjective choice of buildings initially conveys the impression that the author is triggering an explosion from the interior of his work, at first gingerly, later somewhat louder – we’ll speak about the music videos later. But the love of the picture remains. It consists above all in that each shot is very carefully chosen and lasts long enough for the viewer to completely register the image. But this time it doesn’t fit in a meaningful context, for example by being tied to the name of an architect. What ties the pictures together is not apparent, the pictures seem scattered, and yet they form a whole.

Keeping the balance between speech and ‘silence’ was the biggest challenge in this film. The project Photography and beyond has always hinged on a precisely worked out cinematography and the argumentative use of these thoroughly composed scenes within a film. The pictures should narrate and argue, and their sequence should gradually reveal a nonverbal meaning, but one that can be grasped. The sequence is crucial for me; there are no arbitrary pictures, but a progress of understanding. And for me, in this film, meaning is the depiction of a cycle of repetition with the components progress, obliviousness, terror, and a new beginning. In this way, I see the current state of Ulrich Müther’s bus stop in Binz on Rügen Island – squeezed between gigantic public toilet buildings – as a tragic finale in our dealings with the history of modern architecture.

This cycle of repetition is found within an individual work, as well as in the whole film series. In The Airstrip, this culminates not only in the heterogeneity of the pictures, which breaks with the homogeneity of most of the earlier architecture films. The strange, fairy-tale-like voice-over, the suddenly appearing animated components and the music tear the work out of what we expect. This is quite explosive, and you bring it into connection with the image of the atom bomb – a peculiarly disturbing mixture of art and reality.

Expectations would be acceptable only if there were a culture of ‘those who know’. But we have to narrate the world to ourselves anew again and again, because on our spirals of life there are always new facts, for example the weapons of mass destruction. These facts always also reflect the state of the sciences, i.e., of biochemistry and physics; and with the ‘progress’ of the weapons, their use is also depersonalised, ever more anonymous and left to chance. On Tinian, the monuments next to the concrete ditches from which the two atom bombs were lifted into the B-29s bear the names of the bomber pilots; this feels like a coarse deception to me. The pilots didn’t know what they were transporting; rather, they took part in a thoroughly anonymised experiment on human material. Deterrence by means of blanket, random punishment and collateral damage was on the agenda like never before. In no way, incidentally, am I thereby saying that this way of playing fate is worse than a targeted bombardment. Ultimately, people are responsible for their governments, even if they don’t want to have anything to do with them.

That your films translate the three-dimensionality of architecture into a two-dimensional picture becomes clear, at the latest, when meat, ham, clothes and kitchen appliances fly through the picture and look like they have been cut out of a supermarket’s advertising circular. This is almost slapstick and very funny.

They do come from such circulars. My mailbox is the only one in my building that doesn’t have a ‘No adverts!’ sticker. This stuff first made its way from there to my notebooks and then into the film. And there these components represent the pun ‘We are all pieces of meat’, especially in air traffic. Whereby a second interpretation of ‘Duty Free Shop’ packs a punch, too. The Wild West, fun without regret.

And suddenly we’re in a music video. We hear ‘Moth Race’ by the band Kreidler. As a short film titled Duty Free from The Airstrip, Decampment of Modernism Part III, the scene won the prize for the best music video in Oberhausen. What led to this collaboration? And was it clear from the start that this work and excerpts from two others that you made with Kreidler would go into the feature film?

No, nothing was clear from the start. At the beginning of 2012, Andreas Reihse, from Kreidler, asked me to make a video to one of the songs on the band’s new album, because he had long been a fan of my drawings. I had no ideas for drawings, but on the Northern Marianas I had just filmed this long approach through what is now jungle to the 1945 take-off site of the two atom bombs, and I thought the Kreidler song ‘Rote Wüste’ fit perfectly. But the song was eight minutes long and my shot lasted more than twenty. So Andreas made a new mix of the song especially for the video; its length matched that of the footage. And now it constantly runs at full length as a trailer for The Airstrip on YouTube. In the film, only a short excerpt of it is seen. Afterward, ideas for videos to all the songs on their album Den, including ‘Moth Race’, gradually occurred to me, using material from the airport sequences in The Airstrip. All the music clips together now form something like a mini-retrospective of my films.

Interview: Stefanie Schulte Strathaus, January 2014

Downloads

Vertrieb und Produktion

www.filmgalerie451.de/filme/the-airstrip/

Pressestimmen

'Saipan, Tinian landmarks star in German film out in spring' A German filmmaker travelled to the Northern Marianas last year to shoot scenes for a movie that is scheduled for release this spring. Heinz Emigholz, who founded the production company Pym Films in 1978, was on Saipan and Tinian from April 5 to 12, 2012, with colleague and fellow artist Ueli Etter to work on the film The Airstrip-Decampment of Modernism. The two-hour film is the last installment of a series of films about modern architecture that have been shown worldwide in cinemas, film festivals and were especially acclaimed in the United States, said Emigholz. “It will contain several scenes with concrete ruins of Japanese military buildings on Saipan, and “Northfield” on Tinian with its concrete loading pits for the atomic bombs Little Boy and Fat Man,” he told Saipan Tribune, adding that the principal photography for the movie was done all over the world in 62 days. Emigholz, 64, said that his reasons to come to Saipan were manifold. He has studied and written about the Pacific War for decades, and loved the film Anatahan by Josef von Sternberg since childhood. Rat Beach, a story about 1945 Saipan written by William Styron, also piqued the interest of the professor for Experimental film at Berlin University of the Arts. What finally convinced him, however, was the book The Roman Pantheon: The Triumph of Concrete by the late American war veteran David Moore and published by the University of Guam, which he came across when he did a film about the historical and one of the best-preserved structures. “He was a civil engineer and his book is the best about the Pantheon I ever read,” Emigholz told Saipan Tribune, saying that Moore's book also led to his discovery of Moore's website, www.battleofsasipan.com. “I definitely will come back to Saipan and stay some time to work on a book.” When Emigholz returned to Germany following his brief stay in the Northern Marianas, members of the German group Kreidler approached him and asked him to do a video for a track in their new album Den released last Oct. 5. Founded in 1994, Kreidler combines electronic and analog instruments and is categorized by critics, depending on the publication, as electronic music, pop, avant-garde, post rock, ambient, neoclassical, krautrock or electronica. “I listened to their material, liked it and decided to do clips for all seven tracks,” said Emigholz, adding that he used materials shot in the CNMI for the videos of two tracks. He used the shot during the ride to the loading pits on Tinian for the video for Rote Wüste (Red Desert), which was released a month before Kreidler's album came out “and became very popular.” Meanwhile, Emigholz used shots of La Fiesta, the site of the Japanese Banzai attack on July 5, 1945, for the video of Sun. The Rote Wüste video, which has 5,804 views as of press time, can be seen at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rkuIMV-tUGc while the Sun video, which has 2,128 views, can be accessed at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Efw_Zpg71E. (Saipan Tribune, 9.1.2013, Clarissa V. David)