Director Heinz Emigholz discusses THE LAST CITY with NYFF Director of Programming Dennis Lim.

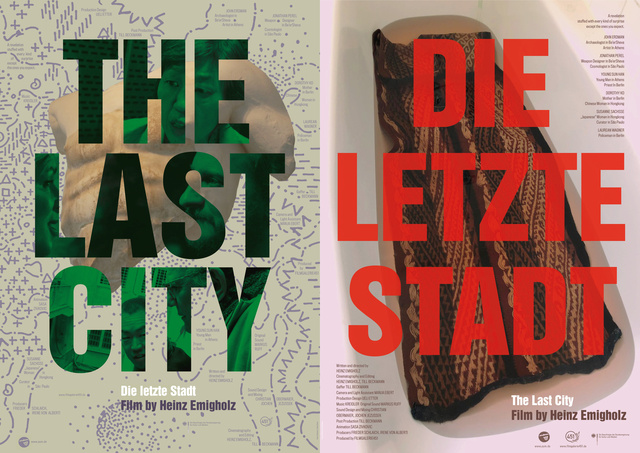

Die letzte Stadt

Die letzte Stadt

Heinz Emigholz

D 2020, 100 min

„A revelation stuffed with every kind of surprise except the ones you expect.“

Ein Archäologe und ein Waffendesigner, die sich in einem früheren Leben als Filmemacher und als Psychoanalytiker gekannt haben, treffen sich in einer Ausgrabungsstätte in der Negev-Wüste und beginnen ein Gespräch über Liebe und Krieg, das sie in der israelischen Stadt Be’er Sheva fortsetzen. Dann beginnt der Film mit wechselnden Darstellern in wechselnden Rollen einen Reigen, der durch die Städte Athen, Berlin, Hongkong und São Paulo führt. Es treten auf: ein alter Künstler, der auf sein jüngeres Selbst trifft, eine Mutter, die mit ihren beiden erwachsenen Söhnen zusammenlebt - einem Priester und einem Polizisten, eine Chinesin und eine Japanerin, eine Kuratorin und ein Kosmologe. Die Dialoge der Protagonisten handeln von obsolet gewordenen gesellschaftlichen Tabus, Generationenkonflikten, Kriegsschuld und Kosmologien. Die Architekturen der fünf Städte dienen als dritter Partner im Dialog der Protagonisten und komplettieren ihre philosophischen und metaphysischen Reisen.

Mit:

John Erdman als Archäologe in Be’er Sheva & Künstler in Athen

Jonathan Perel als Waffendesigner in Be’er Sheva & Kosmologe in São Paulo

Young Sun Han als Junger Mann in Athen & Priester in Berlin

Dorothy Ko als Mutter in Berlin & Chinesische Frau in Hongkong

Susanne Sachsse als “Japanische” Frau in Hongkong & Kuratorin in São Paulo

Laurean Wagner als Polizist in Berlin

Statement des Regisseurs

Der erste Versuch, den Film The Last City zu produzieren fand 2003 statt. Das Projekt hieß damals Tale of Five Cities und sollte von Karim Debbagh für Kasbah Films produziert werden. Die fünf Städte waren Alexandria, Kashan, Buenos Aires, Fez und Houston, Texas: „Ein Episodenfilm in fünf frei kombinierbaren Akten... Es geht ums Atmen und um bedingungslose Liebe, also um Naturrechte, die mit unterschiedlichen Zwängen des Gesellschaftlichen und gesellschaftlich unterschiedlich erzwungenen Opfern in Konflikt stehen... Der Subtext ist Air-Conditioning: alle Formen des Atmens durch alle Stadien der Vergiftung bis hin zur Lähmung, der individuelle Abschied vom Körper in den verschiedenen Gesellschaften“, hieß es in einem Essay, der unseren Antrag begleitete. Nun, wir waren nicht erfolgreich und brachten das wenige Geld für die Realisierung des Projektes nicht zusammen. Ich begreife das als eine Nachwirkung der offiziellen Ausbremsung meines Tuns nach der Veröffentlichung des von mir produzierten Spielfilms Der Zynische Körper von 1991, zu dem es auch kein ausgearbeitetes Drehbuch gegeben hatte, und mit dem ich pleite gegangen war. Die von Freud beschriebene Gefahr „Die Verletzung eines Tabus macht den Verursacher dieser Verletzung selbst zum Tabu“ war Wirklichkeit geworden, oder, wie Frieda Grafe es ausgedrückt hatte: „Wenn ich Ihre Filme mag, besteht die Gefahr, daß Sie nie wieder welche machen können.“

Inzwischen bin ich dreiundachtzig kürzere und zwölf lange Filme älter geworden. Die meisten davon existieren ohne Kommentar und Schauspielerei, im Vertrauen auf eine Kameraarbeit, die ihre Objekte für sich selbst sprechen läßt. Zumeist wurden diese Filme in komplexen Architekturen gedreht, so wie ich es als Kameramann am Liebsten habe. Eine imaginäre Architektur in der Zeit zu konstruieren, war und ist mein Programm. Eine der letzten dieser Architekturfilme, ein monografischer Film zum Werk Eladio Diestes in Uruguay, war zugleich eine ausführliche Drehortsuche für den Spielfilm Streetscapes [Dialogue], der in ausgewählten Bauwerken von Dieste, Julio Vilamajó und Arno Brandlhuber gedreht wurde. Nach fünfundzwanzig Jahren war das eine Fortsetzung von Der Zynische Körper, in dem Architekturen auch schon die Rolle von Protagonisten gespielt hatten.

Das neue, gegenüber Tale of Five Cities stark veränderte Projekt The Last City – Die letzte Stadt setzt da an, wo der Spielfilm Streetscapes [Dialogue] aufhört, ohne daß man von dem Vorgängerfilm wissen muß. Seine Protagonisten haben sich stark verändert und ihre Berufe gewechselt. Aus dem Filmemacher ist ein Archäologe geworden und aus dem Analytiker ein Waffendesigner. Sie treffen sich an einer Ausgrabungsstätte in der Negev-Wüste und setzen ihr Gespräch in der israelischen Stadt Be’er Sheva fort. Dann beginnt der Film mit wechselnden Darstellern in wechselnden Rollen einen Reigen, der durch die Städte Athen, Berlin, Hongkong und São Paulo führt. Die Dialoge der Protagonisten handeln vom Krieg, von obsolet gewordenen gesellschaftlichen Tabus, der Konfrontation eines alten Mannes mit seinem jüngeren Selbst, von Kriegsschuld und Kosmologien. Für eine weitergehende Inhaltsangabe eines nicht nacherzählbaren Filmes fehlt mir der Nerv. Man möge sich der Erfahrung aussetzen und den „Inhalt“ selbst herausfinden. Monothematisch geht es darin jedenfalls nicht zu.

Für mich muß jeder Film der Anfang einer möglichen Analyse sein, die durch ihn in Gang gesetzt wird und dann geschieht. Seine Dauer soll zu einer Zeit des Erfassens und Begreifens werden. Die in vielen Filmen vorgeführte Aufklärung eines Verbrechens ist dabei die vulgärste Variante. Die Banalität dieser Produkte geht auf die Existenz allwissender Drehbücher zurück. Aber verlassen wir dieses Elend, das auf ewig mit dem Segen der Einschaltquoten in seinem Schwachsinn dahinsegelt. Film kann als Erkenntnisinstrument viel tiefer greifen. Er selbst muß zu einem Drehbuch werden, das von der durch ihn möglich gewordenen Erkenntnis geschrieben wird. Ein Drehbuch after the fact, etwa so wie Hellmuth Costard es einmal mit Der kleine Godard an das Kuratorium Junger Deutscher Film exemplarisch geschrieben hat, nachdem sein Film schon abgedreht und fertiggestellt war.

Meine Vision: Der Kameraregisseur tastet die Oberflächen einer monströsen Realität ab, um deren aktuelle Verpeiltheit darzustellen. Die Oberflächen des Wirklichen werden wie Gedanken umgedreht, und die Gedanken werden zu Oberflächen, die gelesen werden können. Verloren geht dabei eine künstlich verrätselte Tiefe, in der das Ende der Gedanken schon vorausgedacht ist. Denn darin gliche die Raffiniertheit eines Drehbuches lediglich dem der Konzeptkunst innewohnenden Gedankenkitsch. Es würde wie diese auf der Stelle stehend verharren – überflüssig wie eine abgelebte Konvention. Wir haben genug davon, auch in dem Sinne, daß es uns anödet. So geht es jedenfalls mir. Die Tabus, die zu brechen sind, liegen auf einer ganz anderen Ebene als auf der des erzählten Skandals oder Unrechts. Die Form der filmischen Erzählung selbst ist zu einem Tabu oder auch Unrecht geworden, das zu brechen ist. Ich habe deshalb nur noch bitterkalte Gefühle gegenüber einer im konventionellen Sinne illustrierend erzählenden Kamera übrig. Ein Kulturkampf, vielleicht, auch ein wunderlicher – aussichtslos sowieso, angesichts der vielen Revolutionen, die keine waren oder sind. But who cares, ich sehe keine Alternative.

Natürlich ist The Last City „geschrieben“ worden. Alles Andere zu behaupten, wäre gelogen. Und zwar in dem Zeitraum von fünfzehn Jahren, in dem die erwähnten Architekturfilme zustande kamen. Die Städte und Themen veränderten sich ständig. Fertiggeschrieben ist der Film dann im März 2018 in Nadur auf Gozo, wo es noch einen wirklichen Frühling gibt, und nicht nur einen erklärt ideologischen. Und mit einer Kameraarbeit im Sinn, die als gleichberechtigter Partner ihre Sprache hinzufügen würde.

Heinz Emigholz, Januar 2020

*

Gut möglich, dass Carlo Chatrian und seinem Team erst nach der Sichtung von "The Last City" die Idee zur neuen Sektion "Encounters" kam - denn wie kein Beitrag sonst gibt Heinz Emigholz' neuer Spielfilm dem wilden Geist der neuen Reihe eine Form. In fünf Städten (darunter: Berlin und São Paulo) kommt es zu fünf außergewöhnlichen Begegnungen (darunter: ein 70-Jähriger trifft sein 30-jähriges Selbst, ein inzestuös lebender Priester seine Mutter), gespielt von fünf Darstellenden, die in jeweils zwei Episoden ganz andere Charaktere darstellen (darunter: Susanne Sachsse und Jonathan Perel). Verbunden ist dieses herrliche Durcheinander durch Emigholz' brillante Dialoge, deren Geist in alle Richtungen sprüht - gegebenenfalls sogar bis ins Weltall, denn zu Kosmologie hat Emigholz neben Waffenindustrie und alternativen Familienmodellen auch noch etwas zu sagen. Und für die Kulinariker unter den Cinephilen gibt es kopulierende Pfannkuchen und eine deutsch-japanische Schuldwurst. Was will man mehr?

Hannah Pilarczyk

*

New Possible Realities: Heinz Emigholz on The Last City

By Jordan Cronk In Cinema Scope

The Last City, the new film by Heinz Emigholz, begins with a confession. “And it was a straight lie when I told you that I had an image that could describe the state of my depression,” admits a middle-aged archaeologist to a weapons designer (played, respectively, by John Erdman and Jonathan Perel, who were previously seen in Emigholz’s 2017 film Streetscapes [Dialogue] as a filmmaker and his analyst). “I made that up.” Part reintroduction, part recapitulation, this abrupt admission sets the conceptual coordinates for a film that, despite its presentation and the familiarity of its players, is less a continuation of that earlier work’s confessional mode of address than a creative reimagining of its talking points. One of Streetscapes [Dialogue]’s key attributes is its autobiographical framework: with conversations sourced from Emigholz’s own therapy sessions, it’s a film that revealed more about the director than anyone could have ever imagined. Just as important, it also inaugurated a return to narrative filmmaking following over two decades of observational documentaries, most of them about architecture. Now fully reinvigorated, Emigholz is freely indulging his impulses, applying nearly a half-century’s worth of experience to the kind of films he had always imagined making. “Do you remember when I told you about the feature film I wanted to make—the one with the five cities?” the archaeologist continues later in the opening scene. “I really didn’t want to make the film at all.”

Another lie. Opening in Be’er Sheva and set alternately in Athens, Berlin, Hong Kong, and São Paulo, The Last City embarks on a roundabout trip through these picturesque locations, taking in their striking landscapes and architecture in a manner (static shots, canted angles) akin to the director’s documentary work. Only now, with no recourse to autobiography, Emigholz has leapt headfirst into the realm of absurdist fiction. Against these backdrops, pairs of alternating actors in different roles engage in extended conversations about love and weaponry, social taboos, generational conflict, war guilt, and the origins of the universe, all in a highly mannered style that emphasizes the essentially irreducible nature of the topics broached. In Athens, an older artist (Erdman) meets a projection of his younger self (Young Sun Han), who fears falling into a life of drug use; in Berlin, two brothers, a priest and a policeman (Young and Laurean Wagner), attempt to reconcile their incestuous relationship with their professional personas and the love of their mother (Dorothy Ko); in Hong Kong, a Chinese woman (Ko) encourages a Japanese woman (Susanne Sachsse, not Japanese) to commit hara-kiri over war crimes perpetrated by prior generations; and, in São Paulo, a museum curator (Sachsse) and a dishevelled cosmologist (Perel) discuss aliens, time travel, and interspecies communication in a kind of subterranean bunker.

Despite the severity of the subject matter, The Last City is a uniquely funny film, due in part to Emigholz’s clever integration of narrative elements into his singular mise en scène. Working with co-editor Till Beckmann, Emigholz cuts around and between the breathless bouts of dialogue, crisscrossing through sequences that occasionally change settings but nonetheless seem to map the entirety of a given location through discrete shots that continually find new ways to frame the performers. Meanwhile, the activity within the individual compositions is downright busy by Emigholz’s standards: marked by ruptures both amorous and violent—including a suicide attempt and one of recent cinema’s most economically choreographed car crashes—the film’s visual syntax and stylized dramatics work productively to heighten the narrative’s self-reflexive sense of humour. Similarly intricate is the film’s sound design, which combines location recordings with Foley effects and the polyrhythmic interplay of the German post-rock band Kreidler, the subject of Emigholz’s 2+2=22: The Alphabet (2017). In auteurist terms, it amounts to a masterful transposition of one artist’s skill set from one mode to another. Outside of Bruno Dumont’s swerve into comedy, it’s difficult to think of a recent creative shift as bold or as inspired as what Emigholz has almost imperceptibly pulled off over these last few years. He’s still making architecture films, only now the material and metaphysical dimensions of his subjects and their surroundings go hand in hand.

Cinema Scope: Can you tell me a little about how this project developed? I think the first time I heard about the film was in 2013, when you were referring to it as The Tale of Five Cities?

Heinz Emigholz: It actually began way earlier than that, around 2002. I wrote something called Tale of Five Cities, but the cities were different: Alexandria, Egypt, Fez, Morocco, etc. Karim Debbagh, a Moroccan producer, wanted to do it, but we didn’t get the money, so I dropped the idea. Over the years the topic changed. I just knew I wanted to have this split experience, with one actor or actress doing double roles as very different characters—if you can call them characters—with very different content. Then two years ago, after Streetscapes [Dialogue], I felt I wanted to do a continuation of that film while going in many different directions. You’ll notice there’s very little in the beginning connecting the two films—you don’t need to know Streetscapes to watch The Last City. But for me it was great to pick something up from that film and dive into new worlds. And from there I chose the cities, all of which I knew very well. We had budget problems: originally I wanted to shoot in Belgrade, but we didn’t get the money. The film had a very small budget. It doesn’t look like it, but that is the case. So we eventually decided to shoot the Belgrade sequences in Berlin.

Scope: So from the original conception the only things that survived are the idea of the five cities and the dual roles?

Emigholz: Yes. I wrote something back then, but I haven’t read it in years. I can’t even tell you what’s written in there. But two years ago is when I began thinking to myself: “What are the five topics you’re most interested in—what is really important to you?” And I thought of these five subjects: family, the division between young and old, weapons design, cosmology, and war guilt. And from there I began to research and talk to people, and then I wrote the script very fast. I think it took three months.

Scope: Although this seems like something of a new direction, prior to your architecture films you made a number of more narrative-driven films.

Emigholz: I made four features prior to my architecture films. The last one was The Holy Bunch, in 1991. That film was shot in 64 days on 35mm and in a lot of countries. I produced it and got totally broke. After repaying my debts, I knew I couldn’t continue in this mode. But architecture was already a kind of protagonist in that film, so I just dropped the actors and continued with the architecture! Before that, from 1979 to 1987, I did three features that people would probably classify as experimental narratives.

Scope: Where do you think this impulse to return to narrative comes from?

Emigholz: I always wanted to return to narrative. I’ve always written scripts, even during the architecture phase. But in the ’90s I was cut short because I went broke. I had a bunch of big productions in the works at that time that never came to fruition. For me the ’90s were terrible: German cinema was down to a negligible state. I don’t recall one film from that time that has anything to say. Even now I’m quite shocked by how stupid and empty it was. At the time, people in Germany laughed at my architecture films—like, “What is this, a slideshow or what?!” But luckily the films gained some success outside of Germany—in Argentina, for example, which has always been very important for me; the film people there are very educated. So I was lucky, since almost nothing was happening for me in Germany then.

But there was also another factor: I taught for almost 20 years at Berlin University of the Arts, starting from 1993 until 2013. And that kept me independent. I didn’t have to beg for money—I could decide what I wanted to do, and architecture films were quite cheap. So I wasn’t dependent on working in television or something, which I wouldn’t have been able to bear. At the same time, when you teach and take it seriously you can’t do a feature-length narrative film because it takes at least one year to produce and finish it, working almost every day. I was also very much involved in building up a new department at the university and I didn’t want to let it go, because I liked it in those days. But now I’m glad it’s over. From 2007 on I had a deal where I only had to teach one semester, so I could film in the summer and still produce work. I’ve always kept filming, which is why there are so many films now, even if they aren’t features. And I wrote scripts, too. So there are scripts I could go on immediately to film, but it’s really hard to get money here.

Scope: So it’s safe to assume you weren’t planning on making architecture films for so long when you began?

Emigholz: No. I wanted to make one film about the subject! And then once I started, it was like, “Well, it’s too long so let’s make a second one.” And from there it piled up—one led to the other.

Scope: Even though it wasn’t planned, there’s something sort of perversely humorous about you integrating these two modes of your filmmaking at this point in your career.

Emigholz: Well, as far the style—at least as it pertains to the cinematography—that was something already in place from probably 1977.

Scope: Right. I’ve read that you began shooting in this style thinking that, however unconsciously, you must be taking after another filmmaker, only to realize later that you had stumbled upon something rather unique.

Emigholz: I think it came out of studying the Russians. It’s not a direct outcome, but thinking about photography as it relates to Rodchenko freed my thinking about cinematography—I was no longer attached to the right angle. I feel I have a special relationship to space, or even negative space. But I guess I just fell into the style from the first feature—or even my first short film, Hotel, from 1975—and I never changed it, because I think it’s right. I mean, in traditional filmmaking this kind of photography is supposed to signify the perspective of a nutcase or something, but for me it’s the right thing to do. Some of these old rules of creating space or continuity are just fucked up—or used up, let’s say!

Scope: What was it about the time period leading up to Streetscapes that prompted this return to a more personal form of filmmaking?

Emigholz: I was actually very sick, mentally sick, around 2014. I had a kind of intellectual friendship with a psychology professor from Tel Aviv, Zohar Rubinstein. We were forming a group around trauma and architecture—a kind of scientific group. During that time I think he found out that my mind was deteriorating, like really going down. I fell into a deep depression and I couldn’t work anymore. So he proposed that I go to Tel Aviv to do a “psychological marathon,” which is what he called it. So we sat down for a week and talked—about personal things, of course, but also about work. And during this discussion the idea for a film about a talk, or a dialogue, came up. And I had asked him if we could record our conversation, which you’re not allowed to do in a traditional analysis. In a real analysis it’s not a dialogue, it’s more that the patient talks and the analyst listens. But I told him that I was afraid I’d forget what conclusions we’d come to, so he agreed to let me record. By the end I was thinking that we had talked a lot about dialogue and filmmaking, and I thought, “Maybe this is the dialogue. Maybe this is the film.” So the whole thing came about without planning to do a film. It was totally unplanned. But what’s interesting is that he knew my films so well. It wouldn’t have worked with somebody else, like a psychoanalyst who hadn’t seen my films. It would have been almost in vain to have this session with someone like that, since it was so much about work and not being able to work anymore.

Scope: And those conversations became what we hear in Streetscapes?

Emigholz: Word for word. I just cut it down.

Scope: And you thought you could apply these words to a narrative in order to speak more openly about yourself?

Emigholz: No, when I look at the film it’s not about me—although it is. I wanted to have a meaningful dialogue that develops something during the course of the event. You need two people who have to tell something which you, as a scriptwriter, must follow even though you have no idea what the end result will be. You don’t know the happy end. In a way, the happy end is the film itself, because if you’re totally mad you can’t finish a film like that. So we don’t talk about healing, but the film itself is a kind of healing. When you look at the film you experience all these strange time shifts: suddenly you’re thinking, “Is this the film they’re talking about? Or is this now the future, or the past? What is this?” I like that idea. The best parts of it reminded me of this Buñuel-like insecurity where time after time somebody turns up and says, “I just dreamt this,” and you never feel you’re on safe ground.

Scope: What was it like casting someone to ostensibly play you? Did you ever consider playing the role yourself?

Emigholz: John Erdman was my first choice, because he knows my work and me so well. I didn’t want to act myself, because I wanted to work the camera. For me the camera is the third protagonist in the film, and it has to be there. I couldn’t trust anyone else. And then I started thinking about who could play the analyst. The year prior I had met Jony Perel at BAFICI through Gastón Solnicki. Jony didn’t say much, but he was engaged in the conversation and what he said I liked. And I liked his voice. I think originally Jony thought the part was for like a five-minute dialogue scene, and when he got the script he was shocked. I think he was ready to give up on the idea but I really got him when I told him, “This is not a script. This is not a fantasy. This really took place.” And Jony, being in therapy himself for a long time, really knows about the process! And then he got interested.

Scope: What do you think Streetscapes provided for you as far as being able to continue in this mode with The Last City?

Emigholz: It really opened up the possibility for me to create a new kind of narrative, with the camera, with a way of editing, with the changing of locations within sentences, and just creating a new way of dealing with narration. And so I thought, “Well, now I’ll try and go further than that.” So this film is not based on real dialogues—it’s a written script. And I’m quite proud of that—that it’s possible to tell stories this way.

Scope: What made you want to return to these two characters from Streetscapes in The Last City?

Emigholz: I decided to begin the film with the crazy illusion that the filmmaker isn’t there anymore, although he makes an appearance and references the film we are in. Now he would be an archaeologist. And I know someone who’s not a weapons designer per se, but he works in a similar industry, and I had a fantasy that the psychiatrist would somehow turn into a weapons designer. I also always wanted to do something in Be’er Sheva, because it’s in the middle of the Negev Desert and it’s a highly industrial city that deals a lot with weapons design and so on.

Scope: Jumping off from that, maybe you can talk a bit about what drew you to these five cities?

Emigholz: I wrote it for the cities. I like the cities, especially São Paulo. And I like Belgrade quite a bit, but it would have been too expensive too shoot there. What I like about Belgrade—and it’s similar to what we ended up highlighting about Berlin—is there’s the new Belgrade and there’s the old Belgrade. There’s a historical part and a totally new part. I like this kind of double-face city. For São Paulo, I like the city landscape and the endlessness of it. I shot the intro to Bickels: Socialism (2017) in Casa do Povo, a Jewish community centre in São Paulo, and I always wanted to go back. And with Athens I knew I wanted an old city, one with a lot of ruins, where people seem to live amongst ancient times. For Hong Kong, a few of my films deal with the Pacific War and WWII, the battles between the Americans and the Japanese. But I wasn’t so aware of the Japanese colonization of China: like the Germans they invaded other countries, robbed and killed their people, and were very racist and cruel. So I began studying the relationship between China and Japan and became fascinated with it.

Scope: Was the pre-production process similar to what it would be for one of your architecture films, in as much as researching and visiting and conceptualizing the locations before bringing in the actors?

Emigholz: Yeah, the actors have no idea about my imagery, and I don’t tell them. We of course go to the locations to shoot the performers in these settings, but on set the actors and I concentrate on the text. There’s no improvisation.

Scope: It’s been a while since you’ve had to cast and work with so many actors. Did you enjoy jumping back into that aspect of filmmaking?

Emigholz: It was fantastic. I like it, I really do. In fact, I acted on occasion in between making films. It saved my ass when I was broke. A German director named Joseph Vilsmaier found me in a bar in Cannes when The Holy Bunch was there. He thought he discovered an actor; he didn’t know I was making films. I was so down, but I managed to make a lot of money working on two of his films. He died recently.

Scope: What’s the process like with the actors on set? You mentioned there’s no improvisation, but presumably not all of them are familiar with your style of filmmaking?

Emigholz: In my mind we’re almost done with that aspect when we finish rehearsals. How I film is, let’s say we have half a page of dialogue: I find a place for the camera, I shoot the actors saying the lines, and then we do it again and again from five different angles, with very few takes. Then in the editing I find my way through these shots. Because there is one rule: I never go back to a shot that I already used. And I think that’s important for a dialogue film like this. The audience should not know where you’ll cut back to. Usually dialogue scenes are shot over the shoulder, with the same three shots, and the actors talk for hours. I think that’s cheating, and it bores me. But here the camera screws itself into a scene, and when I decide on one shot at the editing table, I’ll never go back to that angle.

Scope: What interested you exploring taboos as a subject?

Emigholz: I’m interested in the illogical presence of taboos. For example, incest is a taboo for everyone, young or old. But the reason behind an incest taboo is to not produce birth defects in children. But what about incest between two brothers? Why should that be taboo? It’s illogical. Of course, dealing with these things can be upsetting, but my favourite scene in the film is actually when the mother says to her sons, “People say a family like us does not exist.” And one of the sons says, “See how wrong they can be!” As if what they are is real. I love that. I mean, it’s absurd, but the logical absurdity of the taboo is real too.

Scope: I’m curious how the subjects of cities and taboos dovetailed into the idea to have each actor play a dual role.

Emigholz: I knew I wanted double characters from the beginning, but I really became interested in exploring the idea after I realized that the five cities concept could structurally facilitate a narrative that circles back on itself a second time. It’s a little bit like a cliffhanger: we’ll see a little bit of the story and then we stop at a climatic moment, like say when one of the characters commits hara-kiri, and then we continue on with it later—like a circle. And this second round turned out to be important. It gives so much speed to the movie. When I came upon this idea it became so much fun to write. That said, before we edited it I wasn’t sure if it would work.

Scope: Can you talk a bit about your editing process and how you approach it when working with dialogue as opposed to just images? Is there a difference for you?

Emigholz: Well, the script gives me the timeline, and I don’t change the script, so it was really easy. I didn’t change the order of the cities or anything. My co-editor, Till Beckmann, and I have a good relationship—we work very fast. Let’s say again that we have half a page of dialogue and we have five or six perspectives of that scene, with three or four takes of each. We say to ourselves, first, what would we never use in one of these takes, and we eliminate that one straightaway and go from there. We have so many possibilities, but there’s not much fighting in the editing process because we know what we want.

Scope: Did you find your process changing at all having to shoot these somewhat more elaborate or violent scenes?

Emigholz: First, I don’t think of the cost. I just write it. And then later I’ll make changes if I need to. For example, when the woman in Hong Kong talks about the little girl being run over by a truck, I wanted to shoot that, but it was quite impossible. So instead we decided to re-enact it through this strange little Super Mario-like video-game sequence, which is placed on top of a stretched-out image of Gustave Caillebotte’s painting Boulevard Seen From Above. That’s one of my favourite paintings, but I really destroyed it! This was of course much cheaper than actually shooting the scene in reality. And I really like it that way!

Scope: You say that you don’t think of the costs, but when writing did you ever think that some of the situations were too wild? Do you worry about maintaining the correct tone, or if the audience is wondering if it’s supposed to be funny or not?

Emigholz: Well, I think it’s funny! So I don’t really care if they’re inhibited to laugh or not. But I know what you mean. People think, “Are we allowed to laugh?” And because the film is quite fast and it changes tones very often, there might not be time enough to laugh. But I think it’s important that we take things to a certain point and not overdo it. It has to be subtle, in a way. There’s this heavy voice at the beginning and end of the film that opens up a story that may or may not be fulfilled, but it’s setting a certain tone—like in a fairy tale. But I think the last city, as an idea, is a combination of it all: that there’s actually a solution, or something like a solution. The man speaking in voiceover doesn’t know what city’s he’s in, and in his dream tries to find out. It’s the idea of a solution.

Scope: Do you plan to continue making narrative films?

Emigholz: That’s the main reason I’m on Earth: to develop a new narrative.

Video Extra

Black Canvas FCC / Q&A THE LAST CITY

Director Heinz Emigholz discusses THE LAST CITY with Black Canvas FCC programmer Pedro Emilio Segura.

NYFF58 Talk: Christian Petzold & Heinz Emigholz

about their formative experiences of cinema, how the themes of architecture, history, and capitalism figure in their work, and what they love and hate in film culture right now. Moderated by NYFF Director of Programming Dennis Lim.